I make no apologies for the amount of space taken up in this issue by matters concerning planning, archaeology, heritage and conservation areas. Corsham’s Mansion House and the Bath Road development in Pickwick both invoke key issues about the effectiveness of the concept of ‘Localism’. Planning decisions about Corsham Mansion House are also an important test of the significance attached to Conservation Areas [this year is the 50th anniversary of the creation of the legislation – see article, pps. 10-11]. Fundamentally, at issue is how planning matters impacting on Corsham are dealt with by Wiltshire Council.

As you will know from the last issue, just as we went to press, the Secretary of State announced that Listed Building Consent had been granted, subject to conditions.

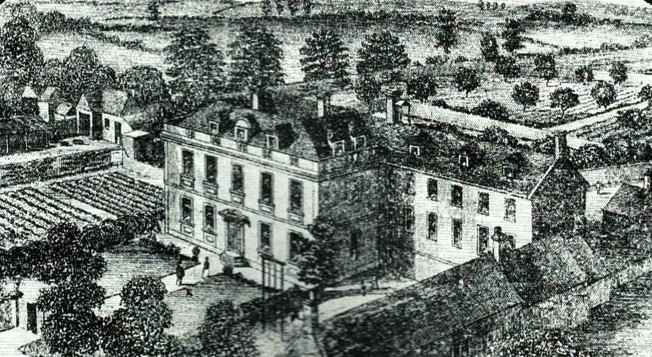

The Mansion House in 1897

The Planning Casework Manager for the Department for Communities and Local Government, wrote to Wiltshire Council on 19th July, as follows:

Paragraph 134 of the National Planning Policy Framework (the Framework) states that where a development proposal will lead to less than substantial harm to the significance of the heritage asset, this harm should be weighed against the benefits of the proposal including securing its optimum viable use. The Secretary of State has considered carefully the proposal, including the objections submitted by the Ancient Monument Society and the Georgian Group, but has concluded that the benefits of the proposal outweigh the harm to the heritage asset. [the underlined and bold fonts are mine]

The conditions were standard and a separate Note was attached setting out the circumstances in which the validity of the Secretary of State’s decision might be challenged in the High Court.

Of course, the phrase ‘less than substantial harm’ begs so many questions. Turning to ‘the Framework’, as noted by one of those in opposition to the scheme as presented by Wiltshire Council, various points were worthy of note and comment:

Paragraph 8 requires where there is a conflict between the proposed development and conservation of a heritage asset, decision-makers must consider whether there is an alternative means of delivery, before weighing those benefits against harm. At the Wiltshire Strategic Planning Committee meeting, Wiltshire Council’s Committee paper did not present any alternative options.

Paragraph 132 requires decision-makers to give “considerable importance and weight” to the preservation of the setting of listed buildings”.

The strong advice from the amenity societies was that far from the over-assertive proposed extension having no adverse impact, it would cause substantial harm.

Paragraph 64 requires that “new development [should] make a positive contribution to local character and distinctiveness” and that “permission should be refused for development of poor design”.

The Wiltshire Council planning officer reported that the demolition of the former library building would have a neutral impact on the conservation area and went on to assert that the proposal (which must, therefore, include the new building) would provide “direct enhancements”. It was difficult to conclude there was anything distinctive or enhancing in the proposal put before the Wiltshire Strategic Planning Committee. If councillors considered the application to be of poor design – or could have been better – or the design failed to take opportunities available for improving the public realm, then the NPPF unequivocally states the default position should be refusal of consent. Corsham had a once in a life-time opportunity to see the former library site and Mansion House brought back to life. Economic vicissitudes do not outweigh material considerations, especially when an alternative method of delivering the regeneration was available. In conclusion, members of the Committee were strongly urged to endorse the detailed exploration of developing the areas to the south (rear) of the Mansion House for an extension, which would deliver the economic benefits all wish to see, while not causing substantial harm to a remarkable building. It was the pragmatic way forward but that recommendation was ignored.

Localism

The Coalition government formed in Britain in May 2010 made localism a core part of its political programme. The Coalition Agreement promised ‘a fundamental shift of power from Westminster to people‘ and said that the new government ‘would promote decentralisation and democratic engagement and end the era of top-down government by giving new powers to local councils, communities, neighbourhoods and individuals‘ (Cabinet Office, 2010:11). In June 2010, Eric Pickles, Minister for Communities and Local Government, declared that his priorities were localism, localism and localism. In December 2010, the government introduced the Decentralisation and Localism Bill, as a key component of the government‘s flagship ‘Big Society‘ policy, with the assumption that localism and decentralisation have a positive effect on community empowerment.

Unfortunately, all too often in recent years the debate and narrative around community empowerment, Big Society, localism and the future of local government and public services has overlooked or merely scratched the surface of the role of local (parish and town) councils. Wiltshire Council should take heed and rather than take the view that ‘nanny knows best’ engage with local councils, not least, where there are issues concerning their heritage ~ see this link.

John Maloney